There is already enough food to feed everyone in the world; those going hungry just lack access.

Global trade moves food from where it is produced to where it is consumed, keeping people fed. Russia and Ukraine are two of the world’s largest agricultural producers, whose food exports account for some 12 percent of total calories traded in the world. The war is wrecking a quarter of global grain trade. What is at stake is an international agricultural trade worth some $1.8 trillion.

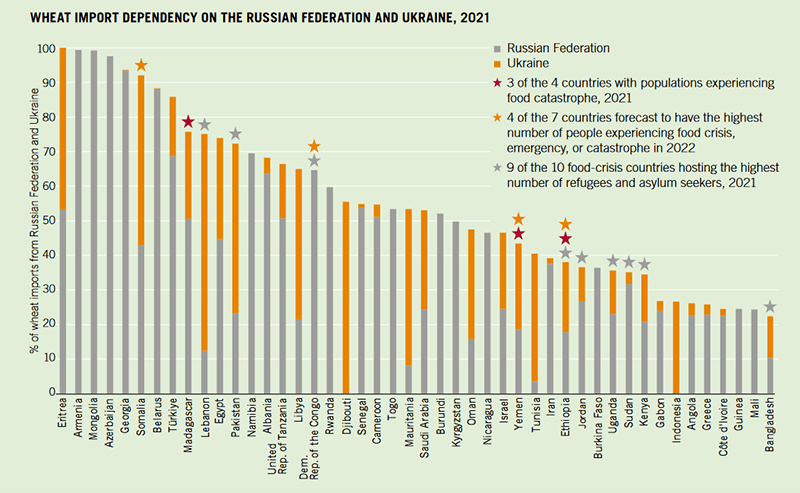

The fallout of this disruption could be devastating. Some 50 nations that rely on Russia and Ukraine for the bulk of their wheat imports—including Bangladesh, Egypt, Iran, and Turkey—have been scrambling to find alternative suppliers.

This situation comes on top of persistent food inflation, which began in the second half of 2020. In March 2022, global food prices jumped to their highest levels ever recorded. Compared with the previous year, prices for cereals were up 37 percent; cooking oils, 56 percent; and meat, 20 percent. As of July, prices have fallen slightly since March, but in June they were still 27 percent higher than in June 2021.

Even before the Ukraine war, fertilizer prices were skyrocketing owing to high demand and the rising cost of natural gas, a key component in fertilizers. The disruption of fertilizer shipments from Russia, a leading fertilizer exporter, is undermining food production everywhere, from Brazil and Canada to Kenya and Zimbabwe, and could lead to lower global crop yields next year. And global food stockpiles are lower than they were before the pandemic.

All of this adds up to greater food price volatility. When the price of food ticks upward, it does not mean simply that people must tighten their belts or pay more for their meals. For those already on the brink of famine, it could literally mean starvation. Food inflation can unsettle markets and even precipitate the overthrow of governments, as it did in Sri Lanka, whose experience serves as a warning to the rest of the world.

A Losing Fight

At the 1974 World Food Congress in Rome, Henry Kissinger declared that in 10 years no child would go to bed hungry. Although his prediction did not come true, the decades that followed marked steady progress against hunger. Unfortunately, though, when 193 countries met at the United Nations in 2015 to commit to ending global hunger in 15 years, the trend was already reversing—the number of undernourished people in the world had started to rise.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, which wiped out two decades of progress on combating extreme poverty and hunger, forcing hundreds of millions more people into chronic hunger. In countries like Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Yemen, the number of people facing hunger jumped by 20 percent between 2020 and 2021.

Globally, 3.1 billion people cannot afford nutritious foods and depend on starchy foods for calories. Based on current GHI projections, 46 countries will fail to achieve a low level of hunger by 2030.

At the outset of the pandemic, countries committed to working together to keep global agricultural trade flowing amid lockdown measures. Now, with panic setting in, signs of protectionism have emerged, as governments begin to impose food export bans to protect domestic supply.

Rising prices have already put even the most basic foods beyond the reach of many poor families across the globe. If the war in Ukraine continues, food inflation will spell greater disaster, especially for poorer countries.

My colleagues and I estimate that between 8 and 13 million more people could become undernourished in 2022–23, with the biggest increases occurring in Asia, Africa South of the Sahara, and the Middle East.

How to Avert Disaster

The war between Russia and Ukraine may seem like the death knell for the hunger goal.

But the chasm between reality and the utopian ideal of achieving “Zero Hunger” should not be a reason for despair. Rather, the goal should serve to hold governments and the international community accountable for fulfilling the universal right to food and ensuring a dignified life for everyone. As international cooperation shrinks amid geopolitical tension, such advocacy has never been more important. This goal is a battle cry to rally support and push countries into action.

So what can be done? The answer is, a lot. Food aid that has kept families afloat through the pandemic must continue. Without strong social safety nets, countries cannot begin to reverse the trend in hunger. Governments are financially strapped and not keen on expanding social safety nets—but they must remember that the generous COVID-19 aid packages, especially across industrialized countries, cushioned the shock of the pandemic lockdowns, which would have triggered a global recession and sent hunger rates soaring.

Vulnerable countries, especially poorer countries that rely on food imports from Russia and Ukraine, should be given immediate financing to buy food for their populations. An emergency fund of $24.6 billion would cover the immediate needs of the 62 most vulnerable countries, which are home to 1.79 billion people. The International Monetary Fund is well positioned to implement this initiative.

Every effort should be made to avoid export restrictions of food and fertilizers. Failure to do so will increase price volatility and price hikes. Imposing export bans is the worst response countries can choose right now.

Governments and investors need more information on market conditions so they can make informed decisions without panicking. More market-monitoring services, like the Group of 20’s Agricultural Market Information System, can increase market transparency.

Rigorous soil testing and nutrition soil maps can help farmers throughout the world learn exactly how much and what combination of fertilizers their land requires. This information can help them use fertilizer more efficiently going forward.

At the same time, we must reduce food loss and waste. Currently, close to a third of all food produced around the globe—enough to feed about 1.26 billion people a year—is lost or wasted at some point in the food supply chain. If we could cut food loss and waste in half, the food supply would contain enough fruits and vegetables to cover the recommended amount of 400 grams per person per day. Inefficiencies along the food supply chain and food waste from the wholesale to the consumer level also have a major impact on the environment. Limiting food loss and waste can therefore help to both fight hunger and reduce environmental harms.

Achieving “Zero Hunger” was always going to be an enormous challenge. This is because ending hunger is not a simple matter of producing more food. Hunger cannot be eradicated unless we tackle the structural drivers that cause it: war, climate change, recession. It’s a tall order. But that does not make the hunger goal the stuff of UN legend. As the previous set of UN development goals showed, such collective commitments influence how countries use and distribute resources. They are also instrumental in raising money to continue the good fight.

Kissinger’s declaration that hunger was unacceptable nearly half a century ago was prescient. Come 2030, if current conditions continue, there would still be at least 670 million undernourished people among us. We may not be able to end hunger by then, but we can stop heading in the wrong direction.

The world will not end in 2030. Nor should the fight against hunger.

Note: Figure shows net wheat-importing countries that get at least 20 percent of their wheat from the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Food catastrophe = IPC/CH Phase 5, emergency = IPC/CH Phase 4, crisis = IPC/CH Phase 3.

This article was originally published in October 16, 2022 as part of the Global Hunger Index 2022 (pp. 18-19).

(Photo by Adrien Taylor on Unsplash)